In September 1811, Alphonse, now definitively released from his clothing employment, sent a detachment by boat from Huningue to Wesel to join the regiment. He travelled to Hamburg, made contact with Hubert and returned to the Huningue depot, bidding it farewell on 20 April 1812 when he left for Cologne with another detachment.

It is worth highlighting the extensive shuffling of personnel at the Huningue depot, which was intended solely for the benefit of the 7th Regiment. Between 1806 and 1812, Alphonse sent three detachments of reinforcements. In 1812, a 5th and 6th battalion were added to the regiment.

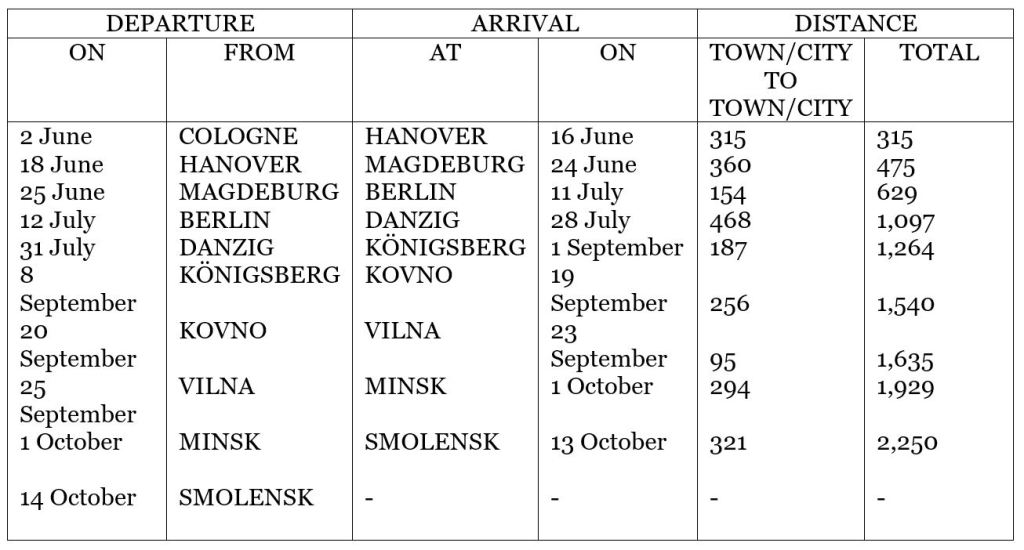

Notice the length and distance of Alphonse’s two major convoys:

– Huningue-Tilsit, August 1806-January 1807: five months, 1,600 km.

– Huningue-Smolensk, April-September 1812: six months, 2,250 km.

The Russian Campaign (1812-1813)

Tsar Alexander formed the Sixth Coalition with England and Sweden under Bernadotte. Having completed his preparations, on 27 April 1812, he sent an ultimatum to Napoleon, who declared war on 22 June 1812.

The Tsar had assembled 300,000 men in two armies, one to the north on the Dvina, under Barclay de Tolly, the other on the Dnieper, under Bagration. He summoned Moreau, the victor of Hohenlinden, Napoleon’s rival, who had been exiled to the United States. The Tsar made him his strategic and tactical adviser. Subjected to this influence, Alexander refused to engage in battle and withdrew in front of the French, thus lengthening their lines of communication and leaving space, time, wilderness and climate to decide his defence.

Napoleon had assembled the Army of Nations: on the left wing, 30,000 Prussians under Macdonald; on the right wing, 30,000 Austrians under Schwarzenberg; in the centre, under Napoleon, the invasion army comprising, in addition to the French, contingents from Bavaria, Saxony, Westphalia, Denmark, Holland, Switzerland, Poland, Italy, Dalmatia and Croatia. For three days (24-26 June), the Grande Armée crossed the Niemen at Kovno, in Lithuania. Five days later, when it entered Russia, it had already lost 50,000 men, 1/6 of its strength, through illness and desertion, without firing a shot.

First, we will follow Hubert with the 7th Light Infantry Regiment and Pierre with the 13th Léger. These two regiments were in the vanguard of the army’s centre, along with General Nansouty’s Cuirassier Division. They passed through Vilna, Disna, Polotsk, Oulla, and on 30 July they reached Vitebsk, from where Pierre wrote his last letter to his mother:

… Even though I am on duty, I had myself replaced to travel to the town and write this draft, which I am doing in a hurry, and to take advantage of the general post office of the army, which I encountered for the first time. There have already been a few affairs, although the 7th and 13th Light Infantry Regiments have not taken part in them. I am mentioning these two regiments because they are the ones in which you are undoubtedly the most invested in.

For eight days I was in command of six companies of voltigeurs to serve with General Nansouty’s Cuirassier Division, in the central vanguard of the Army. This command was very pleasant for me and gave me reason to hope that I could enter into some advantageous engagements, but I was only able to see the Cossacks once, who provided me with a fairly decent horse that I ride in preference to the one I acquired in Hamburg.

… I reserve the right to tell you at another time how we eat, or rather how we procure our sustenance. I have never lacked soup, boiled meat, poultry, butter and all kinds of livestock. Drink consists particularly of brandy, which the poorest people in France cannot stand, but to which we are accustomed; we add water to it. As for beer, it is very rare and if you can sometimes find a few bottles of wine in the large towns, which is usually bad, we pay four, five or six francs a bottle.

In the stretch between the Dvina and the Dnieper, Napoleon thought he had won the battle and captured the two Russian generals at Smolensk, however they escaped him by sacrificing their rearguard in a devastating battle in which the 7th and 13th Light Infantry Regiments took part in the scorched city on 17 August 1812.

Retracing our steps, we follow the brave Captain Alphonse Dandalle on his long-awaited return to the war battalions and his plight as part of the second echelon of the Grande Armée.

Travelling by boat, Alphonse left Huningue for Cologne, where he arrived on 29 April 1812 to find the units in the process of being organised. His company was amalgamated with three companies of the 3rd Infantry Regiment to form the 1st Battalion of the 1st brigade de marche, itself composed of three battalions, two of which were light infantry and one line infantry battalion. Many units were stationed in this town, where military life was bustling. Alphonse’s company exercised six hours a day.

On 2 June 1812, it was time to depart. We accompanied, in echelon, the 7th and 13th Light Infantry Regiments on their march eastwards; we are now following, in the second echelon, Alphonse’s progress with the 1st Demi-Brigade. We join them in Danzig on 28 July, where the 1st Brigade, incorporated into IX Corps, received field supplies from the Grande Armée (bread, meat, dried vegetables) and headed for an undisclosed destination on 31 July.

Since Cologne, Alphonse had not received any news of his wife and sons. However, an advanced depot of the 7th Regiment had been set up in Danzig, where he found Hubert’s among the officers’ trunks, although, Alphonse wrote, ‘nothing is yet established here about the army’s progress, or the results of its achievements’.

Unfortunately, Alphonse’s misery began when he arrived in Königsberg on 1 September. He learned that in the fierce battle of 17 August at Smolensk, the 7th and 13th Léger had been decimated and that his two sons had been killed. He did not dare tell his wife :

I have received no word from either of them. May God have preserved them from all danger in the great affairs that have taken place since the commencement of hostilities and may we obtain good news from them, although, as I have already told you, one must expect everything in these circumstances.

When he arrived at Vilna on 24 September, he continued, with a heavy heart, to arrange how to explain what actually happened:

He (the commander of arms in Vilna) told me that he had nothing to say about Hubert or Pierre, because since then we have endured some serious affairs; this is very distressing news. The thing that afflicts me the most is the fate of our children, about whom no conclusion can yet be reached. However, in these sad circumstances one should rather expect bad than good news, and know how to be strong enough to console oneself in the face of any misfortune. However, may God preserve us from it.

The Russian Campaign of 1812 – Itineraries

The March East of the 7th and 13th Light Infantry Regiments

The March East of the 1st Demi-Brigade

The encounter of the 1st Demi-Brigade with the retreating Grande Armée took place in the vicinity of Vyazma.

On his arrival in Minsk on 1 October, Alphonse, holding back his despair, still expressed doubts regarding the fate of his sons:

In my last letter, number fourteen from Vilna, I expressed my concern about the fate of our children; it is still the same, to say the least, although without causing me as much grief as possible and exerting all my strength to bear the unfavourable news that is always to be expected in such a horrific and cruel war. Are our sons alive or are they not?

I am still not certain. Some say that they were dangerously wounded on 17 August at the affair of Smolensk, which was devastating for two days; others say otherwise. In the end, whatever their fate, if they succumbed on the field of honour, we will have to firmly resolve to bear a misfortune that is almost inevitable in all these dreadful affairs.

On 13 October, at Smolensk, he visited the battlefield, still not willing to tell his wife the whole truth:

Yesterday, on my arrival at this city, accompanied by Captain Courtillon, who was wounded there, we crossed the battlefield of 17 August, close to this city, where we could still observe its ground strewn with unburied corpses. This appalling and distressing sight, for many families, had the most terrible effect on me. Sad memories of my comrades and others of whom I cannot provide you with any actual news, as well as of our sons who perhaps, although wounded, supposedly dangerously, were not unfortunate during their evacuation.

This battlefield, I say, offers to the eyes of those who are not accustomed to war the most frightening spectacle. As for me, and without fear, I considered it a necessary evil to overcome an enemy that is formidable and so difficult to defeat; so difficult, I say, that if the campaign does not end soon by an arrangement or through peace, we will not be surprised to learn that all the officers of the regiment and of many other regiments have to be replaced, because there are hardly any veterans left.

This last remark, which seems to be a premonition, reveals the demoralisation and pessimism, not to say discouragement, of Alphonse and his entourage, who had learnt of the carnage at the Moskva on 7 September (50,000 dead and wounded, 30,000 of them from the Grande Armée), the entry into Moscow on 13 September and the burning of the city.

On 20 August, three days after Smolensk, Napoleon, conscious of the disaster that had befallen this family, awarded the Cross to poor Captain Dandalle. He only informed his family of this in a postscript, hoping – human nature, alas, is like that – the loss of his sons would earn him some advantages!

And here, on 24 October, is his last letter. Alphonse finally acknowledged his misfortune:

I am not reiterating anything else, as there is no point in repeating matters which can only evoke a sorrowful memory, and you will surely have learned, perhaps before I did, all that the disastrous effects of the war have caused us and many others to suffer. Finally, let us always console ourselves for all our misfortunes, as we have done in all past calamities.

At present, and straight away, the order to leave has just been given, without knowing where we are heading, although it is presumed that we will make our way to the regiment, which is alongside the 13th Léger in Moscow or the surrounding area.

Alas, they were no longer in Moscow. They were not aware in Smolensk that on 19 October, Napoleon had abandoned Moscow, hoping to spend the winter further south, in the Kaluga region, and that on 24 October, with this direction obstructed at Maloyaroslavets by a Russian army that he did not dare confront, he ordered a retreat from Borovsk. On 23 October, on his orders, the Duke of Treviso [Mortier] blew up the Kremlin.

At Borodino, the Grande Armée rejoined the route ravaged by its advance on Moscow. Alphonse, caught up in the appalling turmoil, survived as far as Studianka: he was killed by a cannonball as he crossed the Berezina (25-29 November).

The figures give a broad outline of the disaster: 35 to 40,000 men crossed the Niemen again on 10 December at Kovno. The Grande Armée, with the reinforcements that had arrived from Germany in the second echelon (around 100,000 men) had lost 330,000 men in deaths, prisoners or deserters.

In the opposite direction, from Borodino to Kovno, the army resumed the line of stages ravaged when it made its way to the Russian capital. The 26th Bulletin of the Grande Armée is of great interest [in that regard]…

Source : Georges Rousseau, L’épopée guerrière de la famille Alphonse Dandalle sous la Révolution et le 1er Empire, FeniXX réédition numérique (e-book), 1994, pp. 56-65.

Other accounts to read :

> Dedicated to the Imperial Cause – Letters of the Dandalle Family, part IV …

> Officer Boudousquie (18th Line) on the road to Russia, 1812, part I …

> Second Lieutenant Madelin and the 1813 campaign …